OTHER SPECIAL BIBLIOGRAPHIES & VOLUMES

The special, topical bibliographies listed here are new compilations or arrangements that are not separately presented in the 32 parts of the main bibliography ("THE GRAND CANON"). Some have been updated on this website to include corrections and citations gathered since the 2022 publication of Volume 1 of THE GRAND CANON.

Also listed on this page are volumes that are contributions to Grand Canyon–Colorado River history and other studies.

A separate list of special BIOLOGICALLY FOCUSED bibliographies will be found under the "SPECIAL BIOLOGICAL BIBLIOGRAPHIES" tab of this website.

Take note too of the "IN THE WORKS!" section at the bottom of this page.

Bibliography of Native Americans Traditionally Associated with the Grand Canyon. Second Edition. (1 May 2023)

Havasupai Tribe

Hopi Tribe

Hualapai Tribe

Kaibab Band of Paiute Indians, and Regional Paiute Bands (also includes Shivwitz Band of Southern Paiute, San Juan Southern Paiute Tribe, Moapa Band of Paiutes, Las Vegas Paiute Tribe)

Navajo Nation : Diné

Pueblo of Zuni

Yavapai–Apache Nation

Unaffiliated Tribes

Native Americans Generally

This bibliography, based principally on Part 17 of THE GRAND CANON, includes pertinent citations from other parts of the bibliography. It is arranged by tribal group, as shown above.

Bibliography of Administrative and Management Issues in the Greater Grand Canyon Region. Second Edition. (1 May 2023)

I. Grand Canyon National Park (excluding Colorado River)

II. Colorado River in Grand Canyon National Park

III. Lake Mead National Recreation Area

IV. Kaibab National Forest (North Kaibab and Tusayan Ranger Districts)

V. Other Administrative and Private Areas Within the Region

-

- Glen Canyon National Recreation Area (Lees Ferry area only)

- Vermilion Cliffs National Monument

- Grand Canyon–Parashant National Monument

- Pipe Spring National Monument

- Gold Butte National Monument

- State and Municipal Areas and Private Inholdings (Grand Canyon area)

VI. Issues Relating to Boundaries of Federal, State, and Native American Lands

This bibliography, based on Part 13 of THE GRAND CANON, arranges citations by federal administrative unit. The Lake Mead section complements the separately available "Hoover Dam Bibliography" (below).

Grand Canyon Underground. The Bibliographical Record of Caves in Grand Canyon National Park, Grand Canyon–Parashant National Monument, and Vicinity (Arizona) Compiled by Earle E. Spamer

This bibliographical and historical compilation pinpoints individual publications that pertain to, in whole or in part, these caves. There are numerous more caves in the region, of course, but these are the ones that have been mentioned in publicly available publications. The federally administered areas in which they are found are the Grand Canyon National Park and Grand Canyon–Parashant National Monument. Additionally, nearby Arizona Strip locales and a few extralimital areas of regional interest are noted. Only one extralimital site mentioned herein seems to be on lands of Native American jurisdictions. Most of the cave names are informal, their names taken from the publications.

This is not a “guide” to Grand Canyon caves; it is a bibliographical and historical record of published materials that pertain specifically or partly to each named cave. Locations are not given for the caves due to concerns for resource management and cultural sensitivity, although a few of them are very well known even if they are not accessible by the general public. Contact Grand Canyon National Park, Grand Canyon–Parashant National Monument, or the Bureau of Land Management Arizona Strip Office and local sources for up-to-date information pertaining to access restrictions, backcountry permit requirements, and travel conditions.

Mapping Grand Canyon: A Chronological Cartobibliography. By Earle E. Spamer

Mapping Grand Canyon is divided into four major sections. Each concentrates on one of the principal names by which Grand Canyon was called during the past three centuries, which have appeared on maps though of course not necessarily with any degree of formality or consistency: Puerto de Bucareli (1777–1872), Big Canyon (1853–1888), Great Canyon (1853–1879), and Grand Canyon (1868–present).

The Colorado River of the West: Cartographic Styles of the 16th to 19th Centuries. By Earle E. Spamer

Everyone who has had the privilege of river-running the Colorado River knows “where it is.” That was not always the case. For years—centuries, actually—the Colorado (by whatever name it had at a given time) ran all over the place. At first, its course was simple—straight to the sea, just like that. Later, the ingenuity of cartographers, using good, awful, and “inspired” data alike, kinked, curved, and waggled the Colorado across the landscape that is the southwestern part of North America.

While their maps concentrated more on political boundaries, the locations of cities and towns, and the broad generalizations of mountains, seas and straits—done really well, or roughly portrayed, or sometimes made up, based on the “best” information of the day, or levitated straight from the works of other mapmakers so as to make some headway and a few dollars, crowns, or Louis—the tightly confined Colorado River went this way and that, picking up along the way a variety of tributary rivers and creeks (or sometimes not). It was not much of a learning process, but willy-nilly. One had to wait for boots on the ground and oars in the water to create a sensible Colorado River.

This is a cartobibliographical primer on drawing the Colorado River during the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries. It contrasts contemporary understandings of geographical relationships with current knowledge. The examples here focus on the river; how its course, tributaries, and outlet to the sea were depicted over time. In some later cases a finer focus is had on the Grand Canyon region.

Eight basic styles are identified here that describe how the Colorado River’s course was drawn across the North American Southwest, and how its mouth was depicted where the river meets the sea. For each particular style, the maps presented here are chosen from among many similar ones, without particular regard to the absolute range of years of production or publication for a given style, since maps were reused or reprinted for years without improvements to the physical geography portrayed on them. Further, it is not the purpose of this survey to produce a historiographical accounting of these styles.

This volume utilizes illustrations that focus only on the Colorado River region, from maps which otherwise encompass far broader geographies. Users even of these detailed views will surely take note of interesting points or displays that are otherwise not relevant to this survey, which always is one of the pleasures of perusing maps. Although only cropped quadrangles are usually presented, the maps are fully cited from the much more comprehensive Cartobibliography of the Grand Canyon and Lower Colorado River Regions in the United States and Mexico (Raven’s Perch Media).

- Introduction

- Historical Notes:

- Nomenclature for Río Colorado and Colorado River

- Puerto de Bucareli

- The so-called “River of the Sulfurous Pyramids”

- California as an Island and the Gulf of California a Strait

- Basic Colorado River Course Styles—Compared

EXAMPLES

- Insular California

- Peninsular California Displaying Variant Heads of the Gulf

- Colorado River Absent

- Linear Colorado River

- Modified Linear Colorado River

- The Egloffstein Model and Variants

- Parallel Green and Grand Rivers as Colorado Tributaries

- The Colorado’s Bactrian Course Through the Grand Canyon

- Appendix. Selected Early Maps of Historical Importance

The Hoover Dam Bibliography : with appendices: Mike O’Callaghan–Pat Tillman Memorial Bridge; Selected Maps; General Guide to Documentation for Hoover Dam and Boulder City in Historic-Places Registers; General Guide to Commercially Produced 3-D Transparency Products

Although THE HOOVER DAM BIBLIOGRAPHY omits most material pertaining to Lake Mead, see also the separate bibliography of administrative and management issues (above), which includes a section for Lake Mead National Recreation Area.

The Grand Canyon! A Worldwide,Year-By-Year Anthology and Annotated Bibliography of Personal Encounters With the World's Greatest Draw 1540–2022

Introduction: On Foot, In Saddle, and With Motor, Oar, and Paddle

Part I. Primary Explorations

Part II. To, Into, and Expressing the Canyon

Part III. Down (and Up) the Colorado

So much has been written about the Grand Canyon from personal experience that it may be surprising that a comprehensive record of these impressions has never been put together. Never has every reference been compiled—nor for that matter have so many items been forgotten from the very time they were published. Yes, there are bibliographies, but most of them are specialized or embrace the tremendous hail of everything that goes beyond personal records and impressions. THE GRAND CANYON! cites, quotes, and annotates the published records of personal encounters with the Grand Canyon, or accounts told on behalf of those who were there, from 1540 to 2022. Many of the items that are now in the public domain (published before 1927) are quoted from, sometimes at length. Numerous publications are in languages other than English; titles and quotations from them are provided in the original languages and in translation.

This volume documents what is otherwise understood only by intuition or supposition— that the Grand Canyon is an intensely attractive draw, and people have “used” its resources intensely. It goes beyond prose, gathering up the works of poets and the publications that record the work of artists, photographers, musicians, cinematographers, and architects—all of those people who have used their crafts to express their impressions of the canyon. And it has seemed logical to split the main part of this volume into the two principal Grand Canyon venues—arriving and seeing it from the rim and on its trails, and experiencing it along the Colorado River.

NOTE To Federal and Native American Administrators

THE GRAND CANYON! documents the “use” of the lands you manage as a resource in and of itself. Much of it probably has never come to your attention and thus it may offer a new perspective of the breadth of interest and participation that people have had with the Grand Canyon. These items are, each in their own way, reports of activities; and however elegantly or not the experiences are described or portrayed, their value is limited if an audience does not know of them.

This bibliography omits publications that pertain to scientific research and to cultural resources of the Grand Canyon. Thousands of these publications are already cited and summarized in other bibliographies and documentary sources [see this website in particular]. Instead, here are personal reports and perspectives, first-hand or told on behalf of the participants.

The people who are cited in this bibliography are from around the world. They express their encounters with the Grand Canyon through writing, lecturing, painting, sculpting, photographing, filming, composing music and theatrical performances, and designing architecture. In their activities they share their experiences and impart their impressions of visits to the Grand Canyon, briefly and indulgently alike. These people are your authorities on the ways the Grand Canyon is “used,” by the general public mostly, your expert witnesses to personal Grand Canyon experiences.

The writers and poets have communicated in many languages. The prose accounts not in English are translated herein—often for the first time, so they are bound to be newly recovered information. Writers’ abilities to communicate themselves are subjective, of course, but they all are undeniable. The record assembled here provides far more information than has previously been available. It shows how the world has interacted with the canyon, over centuries. It forms a set of authentic references that document the attention to, activities on, and impressions of the lands that are today secured by governmental agencies of the United States and Native peoples.

Complementing THE GRAND CANYON! is a separate volume, with a more readable layout, that presents the quoted texts for the period 1540-1926; these are all publications that are now in the public domain. See under "OTHER SPECIAL VOLUMES" below: "My God, there it is!" The World Encounters the Grand Canyon, 1540-1926.

Contrary Canyon: A Bibliographical Guide to the Grand Canyon's Unconventional Past. By Earle E. Spamer

This volume is the first bibliographical accounting devoted only to the exceptional or eccentric aspects of the Grand Canyon, as delivered through publications. It brings to attention the pool of books, magazine articles, and other productions that do not adhere to widespread conventions about the Grand Canyon’s history and science. With the assistance of web searches, one may find a great many more resources that go much farther into detail about any of the topics listed herein; but these often unsupervised items are ephemeral, so they are overlooked here. This guide is restricted to published records, which generally guarantees that there are multiple, identical copies of a work that will be accessible, somewhere, for a long time.

Contrary Canyon is divided into several chapters. “Ancient Asian Visitors” pertains mostly to the supposed discovery of the canyon by pre-Columbian Chinese venturers. “The Egyptian Cave” is noteworthy not only for its mysterious connection to ancient Egypt but for its longevity in popular media—notwithstanding the claims therewith that the Smithsonian Institution and the U.S. government both are “hiding something” under the guise of supersecrecy. While publications that pertain to “UFOs and Alien Activities” in the Grand Canyon are relatively few, an examination of web-based resources reveals a stunning profusion of “documentary” and speculative items that purport there are bases built by extraterrestrials beneath the canyon, and that tunnels connect them with other bases hundreds of miles away, and so forth; and these are inhabited by “Reptilians” and “Greys,” and other extraterrestrials among us who are subjects unto their own across the web. “Geology Askew” records a variety of reinterpretive explanations for the canyon’s creation and accounts for its various geological treasures: citations under “Incredulous Grand Canyons” pause momentarily on a variety of ways by which the canyon owes its existence, which include the novel “Electric Universe” theory of planetary-scale electrical discharges; there are as well “Exaggerations and Peculiarities” enough to tease the imagination; and there was a decades-long “Platinum Rush,” brought into being when the run-of-the-mill gold rush fizzled. The occasional novel is listed among the publications cited in these chapters. Even though they are by definition “made up,” they each have taken inspiration from—and in some measure give further life to—the categorical subjects in which they appear herein.

Last, the predominant part of this guide, Chapters 5 and 6, is devoted to creationism, which swirls restively, even contentiously, through our present-day culture. No unified guide to the publications that deal with Grand Canyon creationist topics has hitherto been available. The subject is confrontational enough to separately lay out the citations for “Young-Earth Creationism” (Chapter 5), then to present (Chapter 6) those that pertain to counterpoints to young-earth creationism, to old-earth alternatives within the creationism compass, and to historical perspectives on creationism that include the Grand Canyon. Even though the canyon is featured widely, selectively, and repetitively throughout creationist publications overall, this guide does not monitor creationist points and counterpoints broadly; that is not its purpose. The focus is solely on the Grand Canyon and how it is seen by creationist authors and by those who explicate the difficulties of creationist viewpoints in contrast to long-standing, conventional, methodically substantiated science.

Miles and Miles of Mules: An Annotated Bibliographical Record of Grand Canyon's Assistants and Equine Associates (By Earle E. Spamer)

They’re legendary, those mules. For well more than a century, “everyone” has heard about “the Grand Canyon mules” even if they have not been to the Canyon. Riding into the Canyon was something to aspire to. Ride a Grand Canyon mule and die. A lot of riders thought that was their fate once they were on the way down the trail, or so they reported afterward, for heroic effect, or perhaps truthfully—we might never know. Riding into the Canyon was not to be missed for the world, they said, but never again. And even so, mules are not the only quadrupeds to tromp into the chasm. Horses have a history here, too, though the mules have won out in the heavy-lift and most inner canyon tourist categories. The "Miniature Horse Hoax" provides an amusingly interesting diversion. Occasionally, burros and donkeys wandered into the scene as well. Though they are one and the same, many people see them as different animals, perhaps because of the names or perceptions of their uses. One also should never overlook the Canyon's most special burro, Brighty, who deserves his own chapter. The equid history of the Grand Canyon furthermore contains fossil and feral equines, a vigorous and sometimes contemptuous history of the activities of humans, their helpers, and maybe the one-time indigenous equid population. So it’s not just the mules—the Grand Canyon mules—that are rounded up in this annotated bibliography. Their many assistants, associates, and ancestors play as well in this small and sometimes just plain fun slot in Grand Canyon’s history. Climb aboard anywhere and see.

1956 — A Resource Guide to the Grand Canyon Midair Collision of Trans World Airlines Flight 2 and United Air Lines Flight 718, June 30, 1956. Compiled by Earle E. Spamer

Background information with online and bibliographical resources that pertain to the accident and aftermath of what to that day was the world's worst aviation tragedy, when two commercial airliners collided above the Grand Canyon and crashed into its depths. It inspired the first efforts to create air traffic control as we understand it today. The online resources include links to oral history narratives. Appendices include facsimile reproductions of accident reports and the National Historic Landmark nomination. The Landmark was formally dedicated in 2014 at Desert View, Grand Canyon National Park, overlooking the accident scene.

Important Note: An oversight in the original compilation omitted the description and links to the Grand Canyon Historical Society oral history transcript and .mp3 audio file with Tom Sulpizio, June 30, 2014. The oral histories section of 1956 is accordingly emended and is reposted separately here. Use the download button below to access this revised section. A future edition of 1956 will incorporate it in its proper context. (In advance, a revised, Version 2 of the first edition is available on Spamer's academia.edu account by going to this page: https://www.academia.edu/103855202/1956_A_resource_guide_to_the_Grand_Canyon_midair_collision_of_Trans_World_Airlines_Flight_2_and_United_Air_Lines_Flight_718_June_30_1956.)

Version 2 has not been posted to the Raven's Perch Media website because the direct download URL for Version 1 has been widely distributed.

"It was this way ..." The Grand Canyon's Indubitable James White and John Hance: An Introduction and Annotated Bibliography. By Earle E. Spamer

James White’s story—among aficionados of the Southwest he really had but one—is perhaps the one bit of Colorado River–Grand Canyon history that is not really understood. What is known—certainly—is that on September 7, 1867, Mr. White was rescued from a crude raft of logs in the Colorado River at Callville, Nevada, miles below the mouth of the Grand Canyon. Suffering severely from exposure and starvation, once a bit recovered he said he had been all the way through “the Big Canon,” the sole survivor of three who had been prospecting above the San Juan River in Utah. His story was acclaimed, then beaten down, and acclaimed again. He did!—he did not!—go through the Grand Canyon on a raft, and live to tell about it.

In the history of the Grand Canyon, White is conspicuous for having been nearly dead. What if he had healthily survived a Grand Canyon passage? Would he have been acclaimed without argument as the first passenger on the Colorado through the canyon? Could his story still have been dismissed out of hand by those who could see the prob-lems with his remembered scenery and timings? Do we unfairly charge his effective illiteracy against him? One can only dispute.

Then there is John Hance. His story—stories, actually—in contrast to James White are much more well known, even if so much of his life has (until recently) been blended well in the shaker of misreminiscence, or shrouded from truth outright. Truth be told, though, people came from far and wide to see and hear John Hance. For a couple of decades at least he was the human embodiment of the Grand Canyon. After all, by his own admission, he had dug out the canyon in the first place.

For anyone interested in Hance’s own history, there are a variety of retellings and mistellings about his life before and after arriving at the Grand Canyon. The stories kept being retold, revised, condensed, elaborated, and passed along again. But those were largely overlooked in favor of his Grand Canyon experiences, like the time he and his horse jumped over it (almost), or the time that he snowshoed across it atop a heavy fog (almost). And so on. But it was all hearsay; he never wrote any of this down himself.

“It was this way ...” makes up for the lack of a documented compendium of Hance tales. As many as possible have been culled from periodicals and books of Hance’s lifetime, which thus offer a bit more credibility as to the authenticity of the stories. The remainder come from less contemporary sources, long after Hance’s time. All of them, though, experienced editing in the retellings, which of course probably would have suited Capt. Hance very well. After all, he himself stood the stage, with one of the most dramatic backdrops ever; and his tellings changed for each audience, straight-faced, perhaps with a twinkle in the eye. “My mule, Octavia . . . now there’s a story.”

Introduction. Owning the Grand Canyon

Part I — James White

- Introduction

- James White, the Accounts

- James White, the Illustrations

- James White, the Inspirations

- James White: An Annotated Bibliography

Part II — John Hance

- Introduction

-

- A John Hance Sampler

John Hance, In His Words, As Retold (a semi-bibliographical gathering)

Hance Buys a Mule (a verifiable, even if made-up, tale)

-

- About Miss Gardner’s (?) Scrapbook

- John Hance: A Truthfully Annotated Bibliography

Grand Canyon. By Sven Hedin. An English translation of the original 1925 edition. Edited by Earle E. Spamer. Published by Raven's Perch Media.

SVEN ANDERS HEDIN (1865–1952) was a Swedish adventurer best known for his explorations across the Asian continent and for a tumultuous professional life, all of which is beyond the scope of this book. The publications stemming from his explorations are numerous, and he was also widely known for his popular travelogue for young readers, Från Pol till Pol (“From Pole to Pole,” published in 1911) that was translated into many languages. But less well known is the entire book that he wrote about his three-week visit to the Grand Canyon in the summer of 1923, based on letters he had sent to his mother and illustrated with his original artwork. It was published first in Swedish in 1925 with the simple title, Grand Canyon; today this is a scarce volume in the antiquarian book market. It was translated into German in 1926 and Russian in 1928. It never was translated into English, until now. The original 1925 volume is now in the public domain. The translation text and Hedin's illustrations may be freely used.

"My God, there it is!" The World Encounters the Grand Canyon, 1540–1926. Compiled and edited by Earle E. Spamer.

Part I. The Writers

Part II. The Poets

Quotations from publications in languages other than English are provided only in translation. Readers who may need to review the quotations in the original languages will be referred to the more complete bibliography (see farther above), "THE GRAND CANYON! "

FROM THE PREFACE:

This book compiles an edited series of transcriptions (and some translations) of the Grand Canyon visits that have come down to us between 1540 and 1926. The cut-off is not arbitrary, but reflects the fact that the publications to that year are now in the public domain; if they had had any copyright protection, it has lapsed. But 1926 also represents the earliest time when the Grand Canyon was one of the United States’ new national parks, which in itself meant that even more people were drawn to visit the chasm. Visitorship had been ramping up under the prolifically successful advertis-ing campaign of the Santa Fe Railway, which for decades had been enticing its ridership to stop by the canyon—if indeed it was not the principal destination. The railroad drummed it into the collective consciousness of Americans of every traveling caste, whether they were aboard parlor cars and upper berths, or among the steerage class of those who bought only a seat. Even so, some of the early visitors arrived on their own, overland; and if they published anything about their experiences, it is also here.

Here I quote from early visitors’ encounters with the Grand Canyon. If they had little to say, well and good, but those who gushed at length have had to be accommodated as well. Most were enthusiastic, as we might hope they would be, but there were a few who groused of their experience. They are all part of one story, a compilation of which has never before been made. There are anthologies, of course, that delve into a few of the works cited herein, but often even they curtail some of the additional interesting remarks that the writers had made. But I have no intention of replicating every word that they have written—especially those of the pioneer chroniclers, Balduin Möllhausen, Joseph C. Ives, John Wesley Powell, and Clarence E. Dutton in particular, who wrote entire books. I instead have had to arrange a tran-script of worthwhile parts of their texts, which deliver specifically personal observa-tions of their encounters with the Grand Canyon, going further than many of the time-honored (perhaps worn-out) series of quotations, although for comprehensiveness I must also embrace those exhausted scripts.

Beyond the luminaries, many if not most of the authors quoted here will be unknown; or perhaps just forgotten in the passage of years. Some were brief; others elaborated at such great length that the more essential accounts of their experiences had to be culled from even longer texts. They report observations, but better yet many of them go into personal reflections. Those who wrote in languages other than English are translated here, usually for the first time.

Despite the tedium of reexpression that one will encounter in this book, each of the hundreds of people quoted herein had taken the time to put their experiences on paper. A lot of them were indeed original, each in their own way; and a few were honest enough to credit any quotations they made. Some were very good at crafting their narratives; a few are stellar examples. And others, well, read on and discover them, too . . .

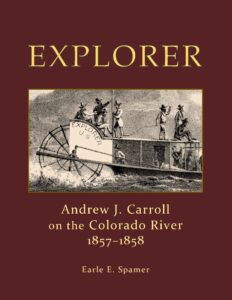

Explorer : Andrew J. Carroll on the Colorado River, 1857–1858. By Earle E. Spamer

including Transcriptions from the “General Report” of Lt. Joseph C. Ives’ Report Upon the Colorado River of the West (1861); and Translations from Balduin Möllhausen’s Reisen in die Felsengebirge Nord-Amerikas bis zum Hoch-Plateau von Neu-Mexico (1861)

FROM THE PREFACE

The story of Lieutenant Joseph C. Ives’ expedition up the Colorado River in 1857–1858 with the steamboat Explorer is well known, well told, and, well, old news. What this book brings to light, however, is Andrew Carroll. He was the engineer who ran the boat’s engine; he also put its parts together in an improvised dry dock dug into the clay of the Colorado River delta, and he may well have helped build the thing in Philadelphia. Ives had occasional things to say about Carroll in his “General Report,” the first part of the 1861 government publication about the expedition. So did fellow voyager Balduin Möllhausen, who wrote his own book about the expedition, in German and published commercially in Leipzig, also in 1861, which has been largely hidden from readers of English. Their sparse remarks about Carroll are dispersed within long texts, and although lots of things have been written about Explorer’s expedition, the engineer has been ignored, save once in a while for his name, who until now did not even have a given name to go along with his surname. He was sketched by Möllhausen, and those little pencil drawings, still owned by family members in Germany, were fortuitously included in a 1995 book about Möllhausen’s artwork from the Colorado River expedition. So while we have an idea of what Carroll looked like, we have lacked a united story about him.

This book does not presume to retell the Ives expedition, so meticulously told by Ives and Möllhausen and recast by historians, professional and avocational alike. It is instead a précis of Carroll’s perspective of things; a story never gathered. On the Colorado, we rely wholly on Ives and Möllhausen since Carroll never wrote about his adventures. Ives kept to the factual details of duty in writing about Carroll. Möllhausen wrote more personably and at greater length, but his rendition has never come down to us in English, except for excerpts, and those were not about the engineer. It’s a shame, because Carroll’s Colorado River story is a remarkable one, brief as it is. Here was a young man, an Irish immigrant in his mid-twenties, sent with a boat kit from Philadelphia to the mudflats of the Colorado River delta (by way of Cuba, Panama, and California ports), where he had to get the sea-weathered pieces into shape (literally), put the kit together with its three-ton boiler and engine running, and then handle its controls under the orders of the hired captain—orders that changed frequently because of the fickleness of the untamed Colorado’s currents, shallow bottom, and obstructions. For a man used to Philadelphia’s gently tidal, unrocky Delaware River, this was something altogether different. Carroll, according to Ives, thought the Colorado was “the queerest river to run a steamboat upon.”

Without his expertise the expedition could not have continued with its planned landward venture that took Ives and part of his command to the Grand Canyon. So even though Carroll never got to see the canyon, he made it possible for the first exploratory expedition to reach it—and more importantly, to publicize it through word and art. True, others would have gotten to the canyon, eventually, but Carroll served as a shipwright and engineer and followed the hails of the pilot above his head. He delivered in one piece to their embarkation point at Beale’s Crossing the international group of Lt. Ives, Dr. Newberry, Herren Möllhausen and Egloffstein, and the soldiers of the land expedition.

Specifically to place Explorer and its engineer in the light of historical acknowledgment, both Ives’ and Möllhausen’s writings are here specially brought together for the first time. My own contribution has been to learn about the man and the firm that made Explorer. This book celebrates Andrew J. Carroll and his new-found part in the history of the Southwest and of Philadelphia.

Balduin Möllhausen's Grand Canyon: An English Translation from Chapters 21–25 of Travels into the Rocky Mountains of North America to the High Plateau of New Mexico [Reisen in die Felsengebirge Nord-Amerikas bis zum Hoch-Plateau von Neu-Mexico] (Leipzig, 1861) with a transcription of coinciding parts from Chapters 6–8 of the “General Report” of Lt. Joseph C. Ives’ Report Upon the Colorado River of the West (1861). Edited by Earle E. Spamer.

This comprises the first complete English translation of the beginning of the land expedition, March 23-April 15, 1858, under the command of Lt. Joseph C. Ives, which reached the Grand Canyon at Diamond Creek and Cataract Creek. It complements Ives' own General Report (1861) with additional detail, exploratory notes and illustrations that did not appear in Ives' volume.

The Colorado River expedition, and the land expedition from Grand Canyon to Fort Defiance, New Mexico Territory, and beyond, are not a part of this translation.

FROM THE PREFACE:

HEINRICH BALDUIN MÖLLHAUSEN (1825–1905) left Germany for the first time in 1849 to hunt in the American Midwest, where he supported himself with the odd job of clerking or commercial painting. Two years later he met up with Friedrich Paul Wilhelm, Herzog von Württemberg, better known in American history as Duke (or Prince) Paul Wilhelm of Württemberg, who with a small entourage had set out to explore the Rocky Mountains. Möllhausen asked to join him, and served as a draftsman. They reached Wyoming, but on the return trip Möllhausen was left behind when there was no more room in a mail coach that took the duke away from a snowstorm that had killed their horses. Balduin barely survived, alone on the prairie for several months, and eventually was rescued by Indians. He later rejoined the duke in New Orleans and returned home to Germany. He was soon introduced to the great adventurer–geographer Alexander von Humboldt and met Carolina Seifert, the daughter of Humboldt’s private secretary—or the unmarried Humboldt’s own daughter, if some would have it—whom he later married. From then on, Möllhausen was a keen follower of his mentor, and Humbolt provided prefaces and salutary promotions for Balduin’s publications.

His experiences on the prairie gave him a taste for further adventures promised in the American West. With a letter of introduction from Humboldt, Möllhausen returned to America to see if he could join one of the western government-sponsored expeditions then being planned. He was assigned as a draftsman for the 35th parallel Pacific Railroad survey of 1853–1854 under the command of Lt. Amiel Weeks Whipple, which passed through the area south of the Grand Canyon, eventually arriving on the lower Colorado River and proceeding to the west coast. He also provided illustrations for Whipple’s final report (1856). Back in Germany again, he also published his own account of the expedition in 1858, Tagebuch einer Reise vom Mississippi nach den Küsten der Südsee [Diary of a Journey from the Mississippi to the Coasts of the South Sea (Pacific Ocean)], which has seen reprintings and translations.

In 1857, Lt. Joseph C. Ives, U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers, who had also accompanied the Whipple expedition, invited Möllhausen to join him again, on an expedition that this time Ives would command, as the expedition’s illustrator and assistant in natural history. After the conclusion of this expedition he returned to Germany for the final time, where he turned out in 1861 his Reisen in die Felsengebirge Nord-Amerikas bis zum Hoch-Plateau von Neu-Mexico [Travels into the North Ameri-can Rocky Mountains to the High Plateau of New Mexico]. This expedition was (officially) to ascertain the head of navigation of the Colorado River, though it also investigated the extent of Mormon incursions into the regions south of Utah. Once the head of navigation was determined on a trip upriver in the Explorer, a small steamboat built in Philadelphia just for this expedition, Ives divided his command into two groups; one returned down the Colorado River, the other, under Ives, traveled eastward overland. Although some intentions were had to explore other areas, the group finally concluded its work at Fort Defiance, New Mexico Territory.

At the conclusion of the river expedition, Möllhausen accompanied the overland party, which became the first to purposely reach the Grand Canyon in an attempt to ascertain more surely the geographical relationships of the region, most importantly the coordinates of the confluence of the Little Colorado River with the Colorado (which they failed to accomplish due to the impassable canyons and side canyons).

Ives’ formal report was published as a U.S. Congressional document in Washington, D.C., in 1861. The significance of Möllhausen’s work to Grand Canyon–Colorado River history is that it predates the release of Ives’ formal report, by several months at least; it constitutes the first-published comprehensive accounting of explorations on the Colorado River and in the Grand Canyon. It also provides details and perspectives not included in Ives’ report. It is unfortunate that his Grand Canyon story, at least in his own words, has been lost in the backwaters of canyon history, having lacked a translation that would have made it accessible to English-speaking readers. This volume offers an expedient answer to the problem, at least until such time that a more proper historiographical study of this part of the expedition is produced by scholars in the field.

The Leipzig Imprints of Balduin Möllhausen's Reisen in die Felsengebirge Nord-Amerikas bis zum Hoch-Plateau von Neu-Mexico (1860, 1861): Bibliographical Notes. (By Earle E. Spamer)

Balduin Möllhausen’s Reisen in die Felsengebirge Nord-Amerikas bis zum Hoch-Plateau von Neu-Mexico, unternommen als Mitglied der im Auftrage der Regierung der Vereinigten Staaten ausgesandten Colorado-Expedition (‘Travels into the Rocky Mountains of North America to the High Plateau of New Mexico, undertaken as a member of the Colorado Expedition on behalf of the United States Government’) was issued under two imprints in Leipzig, both consisting of two volumes. One imprint is that of Otto Purfürst (undated and presumed to be 1860), the other is that of Hermann Costenoble (1861). Alexander Edelmann of Leipzig was the printer for both imprints as well as the lithographs in those volumes.

The Reisen is Möllhausen’s account of his participation in the Colorado River exploring expedition under the command of Lt. Joseph C. Ives during 1857–1858. The expedition ascended the Colorado River in a purpose-built steamboat, from the river’s mouth in the Gulf of California, to Black Canyon. After nearly wrecking the boat there, a brief exploration by skiff reached the confluence of Las Vegas Wash, not far upstream from where today stands Hoover Dam. Returning to Beale’s Crossing, a land component of the expedition left the river, traveling eastward to Fort Defiance, New Mexico Territory (in today’s Arizona). On that trek they visited the Grand Canyon twice — first a descent to the Colorado River in Peach Springs Canyon and Diamond Creek, and second, a partial descent to Cataract Creek (Havasu Canyon).

The U.S. Congress published Lt. Ives’ formal report of the expedition in 1861, which appeared after the Möllhausen volumes (and after Ives had defected to the army of the Confederate States of America). If the presumed date of the [1860] imprint is correct, it demonstrates that Möllhausen’s memoir on the Colorado River expedition was published perhaps nearly a year before Ives’ Report reached its readers and libraries.

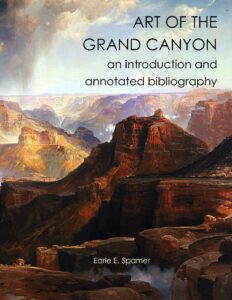

Art of the Grand Canyon: An Introduction and Annotated Bibliography

Art of the Grand Canyon is a historical and bibliographical resource, but it also means to be an “interesting read” specifically for the audience of Grand Canyon historians and aficionados. The Introduction is a very brief, admitedly arbitrary, primer of Grand Canyon art for readers who may not be very familiar with the subject, highlighting some usual and some appealingly unusual aspects about well-known and obscure artists alike, and a few of their pieces. It also finds some new perspectives and makes a few comparisons that might be thought-provoking, perhaps unrealized.

The annotated bibliography gathers citations for publications, beginning in 1853, that in some way mention or illustrate the work of Grand Canyon artists between 1851 and 2023. It serves as a documentary effort that confirms the breadth and depth of artistic interest in the Grand Canyon. It also introduces numerous artists who have not had the privilege of being “recognized” in the world of art, such as those whose work was contributed “on the fly” to various journals and magazines, who are not acclaimed artists in their own right.

There seems to be no end to artists’ interest in an admittedly challenging subject—the canyon—and the appearances of these works in magazines and books, whether only by mention or illustration, maintains a steady pace. There are many “Grand Canyon art books,” too. One has only to look at the front matter or specific chapters within them to find information about, and examples of, the work of renowned Grand Canyon artists—for example, Thomas Moran from the “old school,” Bruce Aiken from the present, and Gunnar Widforss in between—all of them as different in concept, media, and perspective as there are moods of the canyon itself.

It is beyond the purpose of this project to offer criticism; its objective is to present a motivatingly different introduction to Grand Canyon art, and to make published information known. As more and more items are found, they will naturally continue the documentary effort, but surely they will also expose new or forgotten works that run the gamut from monumental to distressingly poor. Anyway, the Grand Canyon always beckons—challenges—those who come to portray it with brush, pencil, crayon, or chalk, even with media such as fabric, clay, glass, and metal.

Art of the Grand Canyon is a new contribution to the history of the Grand Canyon; one that is hopefully interesting for things in it that may not have been realized by its Grand Canyon audience, and in its accounting for the variety of things that have been published that have something to do with Grand Canyon art.

Introduction. “Try again, Daingerfield.”

Trying Out the Canyon: First and Early Samples of Grand Canyon Art

1851 — Richard Kern

1858 — Balduin Möllhausen and Friedrich Wilhelm von Egloffstein

About 1872–1875 —Various artists, for J. W. Powell

1872–1873 — William Henry Holmes and Thomas Moran

1875 and later — Edwin E. Howell

1875 and later —Frederick S. Dellenbaugh

1891 — Henry Moubray Cadell

Turn of the Century — Thomas Moran

1903 — François E. Matthes

1906 — Louis Akin

1923 — Sven Hedin

Reusing and Reimagining Illustrations

An Unusual Piece of Government Artwork

Part 1. Complete Bibliography Arranged by Author of Publication

Addendum: List of Catalogs and Exhibition Publications

Part 2. Selected Bibliography Arranged by Names of Artists

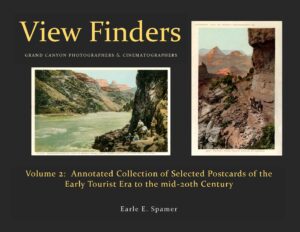

View Finders: Grand Canyon Photographers and Cinematographers (By Earle E. Spamer)

Volume 1: Introduction and Annotated Photobibliography and Filmography

Volume 2: Annotated Collection of Selected Postcards of the Early Tourist Era to the Mid-20th Century

View Finders is a new contribution to the history of the Grand Canyon; one that is hopefully interesting for things in it that may not have been realized even by its Grand Canyon audience, and in its widely ranged accounting for the variety of things that have been published that have something to do with Grand Canyon photography and cinematography.

There seems to be no end to photographers’ interest in an admittedly challenging subject—The Canyon—and the appearances of their works in magazines and books maintains a steady pace. The talents and opportunistic stabs of those who work with photographic imagery of all kinds, over the years snapping shutters, cranking cameras, and electrically panning scenery, corresponds to the efforts of thousands of writers over the years who scribbled, typed, and tapped—all of whom, spontaneously or deliberately, have had (somehow) to capture or express the Grand Canyon.

This compilation should be an inspiration for other work, too. It is beyond the purpose of this project to offer criticism; its objective is to present a motivatingly different introduction to Grand Canyon photographs and films, and to collate and make known as much published information as possible about these subjects. These two volumes comprise a documentary record, but see them also to consider new projects about Grand Canyon’s picture makers—and that marvelous panorama always just called “The Canyon.”

View Finders — Volume 1: Introduction and Annotated Photobibliography and Filmography

The annotated photobibliography and filmography gathers citations for publications beginning in 1872, that in some way mention or illustrate the photographic work of Grand Canyon photographers and cinematographers on the spot between that year and 2023. It serves as a documentary effort that confirms the breadth and depth of interest in the Grand Canyon. It also introduces numerous photographers who have not had the privilege of being “recognized,” such as those whose work was contributed “on the fly” to various journals and magazines, who are not acclaimed photographers in their own right. The Introduction means to be informative specifically for the audience of Grand Canyon historians and aficionados. It is not a historiographical treatment of the subject, an admittedly arbitrary and teasingly brief primer on Grand Canyon photography and cinematography for readers who may not be very familiar with the subject. A brief illustrated section highlights some usual, and mentions some appealingly unusual, aspects about well-known and obscure photographers alike, and a few of their products.

This volume complements the separate publication, Art of the Grand Canyon (Raven’s Perch Media, 2023).

- Grand Canyon’s View Finders: An Introduction

- Some Views, Found — A Sampler

- Part 1. Photobibliography Arranged by Author of Publication

- Part 2. Selected Photobibliography Arranged by Credited Photographer

- Part 3. Filmography Arranged by Attributable Source

- Part 4. Selected Filmography of Action and Documentary Films Arranged by Title

- Appendix 1 — General Guide to Commerically Produced 3-D Transparency Products

- Appendix 2 — General Guide to Commercially and Governmentally Produced Stereographs

- Appendix 3 — The Underwood & Underwood Stereographs “Grand Cañon” Boxed Set (ca. 1904–1908) [illustrated]

View Finders — Volume 2: Annotated Collection of Selected Postcards of the Early Tourist Era to the Mid-20th Century

This volume takes the opportunity to display and compare a selection of postcards that are in the public domain, as a historical, artistic, and cultural survey. While postcards are an obvious genre of “photographs” ideally suited for View Finders, a systematic accounting of them is avoided simply because there are thousands produced by numerous commercial and specialty publishers, as well as small-run knock-offs by businesses and entrepreneurs. Even the very large collections held by academic institutions each is quite different in content. There has until now been no such compilation for postcards of the Grand Canyon and nearby locales. In no sense is this an all-inclusive study of these regional postcards; it is not—cannot be—an inventory of canyon area postcards. There are many more that the author has seen, too, but has no copy to reproduce; beyond that, there are unquestionably hundreds of which he is unaware.

Illustrated herein are 359 postcards and 14 excerpts from postcard strips and miniature photo sets. The separate Table of Contents for the 219 plates of illustrations delineates the geographic and topical arrangement of these products in this volume. A few postcards show scenes near the Grand Canyon, which locations are included for their historical perspective as well as for their parts in regional history and tourist interest—the Kaibab Plateau, House Rock Valley, and the Navajo Bridge on the east, and the Grand Canyon portion of Lake Mead far to the west.

This compilation is meant to be an interesting historical perspective of the early years of Grand Canyon travel. It serves also as a documentary effort that confirms the breadth of commercial interest in advertising the canyon and those who provided transportation to it or amenities once there. It takes opportunities to study special differences between cards, some of which reflect variations of production methods. A few highlight cultural and social stigmas, such as the posing of Native Americans with indifferently incorrect explanatory notes, or the case where artistically added women on one hotel lobby photo are all replaced by men in another version. These all are works of their times.

For each postcard in this volume, its explanatory text (if any, usually on the card’s back) is transcribed. The reader may notice that many legends were copied or re-edited for use on other cards; sometimes they do not even have any reference to the image on the front of the card. In some cases the legends may even confuse the reader into thinking that they do describe the photo. Other legends include quotations from different sources, which although they are not usually credited an attempt has been made herein to identify those sources. Legends can be literarily effusive, and it is occasionally probable that some elemental phrases used in legends have been borrowed, whether it be from a producer’s own travel literature or from the writings of a well-known writer. Dates of copyright are given when indicated, although most cards lack dates; and when a card has been mailed the year is noted to help indicate at least when it was available. A separate section of this volume, “Postcard Messages From This Collection,” is devoted to those cards that had been mailed and on which messages had been written by the card’s sender.

- Introduction to This Collection

- Index to Postcard Views Credited by Publisher, Producer, Distributor, or Photographer

- Postcard Messages From This Collection

- Postcards [The Plates section includes its own geographically and topically arranged table of contents]

IN THE WORKS!

Soon!

"TOO NUMEROUS TO NAME": Noteworthy (and Unfamiliar) People of the Grand Canyon: an annotated biographical bibliography of historic connections, individual accomplishments, records of peculiar or transient interest, and notable visitors since 1540.

Unscheduled

THE GREAT DIVIDE. Stalking the Lower Colorado River, 1874-2024: a bibliographical witness to the division and depletion of America's grandest river. [dates of coverage subject to change]